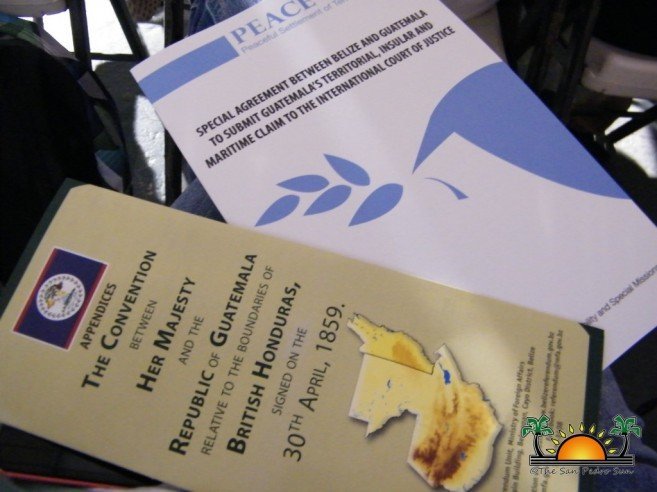

In 2008, at the urgency of the Organization of American States, Belize and Guatemala signed a Special Agreement (compromis) to settle the long-standing territorial dispute between both countries at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In the agreement, Belize committed to settle the matter at the ICJ after the participation of Belizeans in a national referendum set for April 10, 2019. However, the government never consulted Belizeans prior to signing the Agreement, and the definition of the Belize-Guatemala territorial dispute in such document has since then been the subject of much criticism. The Special Agreement has garnered so much attention that attorneys in Belize are preparing to challenge it at the Supreme Court, to question its legality, validity and constitutionality.

The Special Agreement explains that a referendum must take place in both Guatemala and Belize on whether or not to submit the Guatemalan claim (territorial, insular, and maritime) to the jurisdiction of the ICJ. If Belizeans vote in favour of going to the ICJ, the case will be taken to this court, based on the description in Article 2 of the Special Agreement. This Article states that ‘The Parties request the Court to determine in accordance with applicable rules of international law as specified in Article 38(1) of the Statute of the Court, any and all legal claims of Guatemala against Belize to land and insular territories and to any maritime areas pertaining to these territories, to declare the rights therein of both Parties, and to determine the boundaries between their respective territories and areas.”

The words ‘any and all legal claims of Guatemala against Belize,’ is what have Belizeans and lawyers somewhat puzzled as this indicates no certainty of what Guatemala really wants. Well known Belizean lawyer Richard ‘Dickie’ Bradley briefly spoke to the media in regards to the legal challenge that will be launched against the Special Agreement. “There will be a formal legal challenge in relation to the legality, validity of the Special Agreement, which will take place very soon,” said Bradley. He explained that, ‘There is a principle in law that a government can sign agreements with other countries and even enter into treaties. That is a part of the role of the executive, so the Minister of Foreign Affairs can sign treaties with other countries. There are, however, some difficulties with certain treaties, and it appears that the Special Agreement is one of those treaties.’

The senior attorney indicated that the result of the signing of such Agreement without the consultation of the Belizeans is now pressuring them to vote in a referendum to take the Guatemalan claim to the ICJ. Bradley pointed out that this is the only involvement of Belizeans in the matter and emphasized that whatever decision is reached by the ICJ is final and binding. “The Special Agreement also involves the possibility that the boundaries of Belize can be adjusted by this court,” explained Bradley. “We have no say in this compromise, it has already been signed, sealed and delivered and turned into a treaty. Even though it is duly executed, it may turn out that the government has no authority to execute such agreement.” According to him, the Special Agreement was ratified by the Belizean Senate in December of 2016 turning it into a treaty with Guatemala, something allegedly unknown to many Belizeans.

When the case is brought before the Supreme Court, Belizean attorneys will be asking the court to declare that the document is unlawful and cannot be followed. The Supreme Court deals with the rights of Belizeans and equally deals with the constitutional requirements as to how things are done at certain levels by the government, the organs of the state and government officials. Bradley added that the Supreme Court has the jurisdiction to say whether or not the Special Agreement is infringing on certain rights of Belize and the constitutional requirements as it applies to the boundaries and state of Belize.

While the legal team prepares its case to take to the Supreme Court, of importance to note is that the Special Agreement makes no provision for a ‘No’ Vote. If Belizeans vote No in the April referendum, it simply means that the matter will not proceed to the ICJ. It will leave the door open for any Belizean government to set another date for Belizeans to vote again.

Guatemala and Belize were initially scheduled to hold referendums simultaneously in 2013, but after this attempt failed, both countries were allowed to do it on different dates. Guatemala held its referendum on April 15, 2018, garnering a ‘Yes’ vote in support of the ICJ idea. Despite just a 26.33% participation of the seven million eligible voters, almost 96% of this low turnout voted for the ICJ, while less than 5% voted against it.

Share

Read more